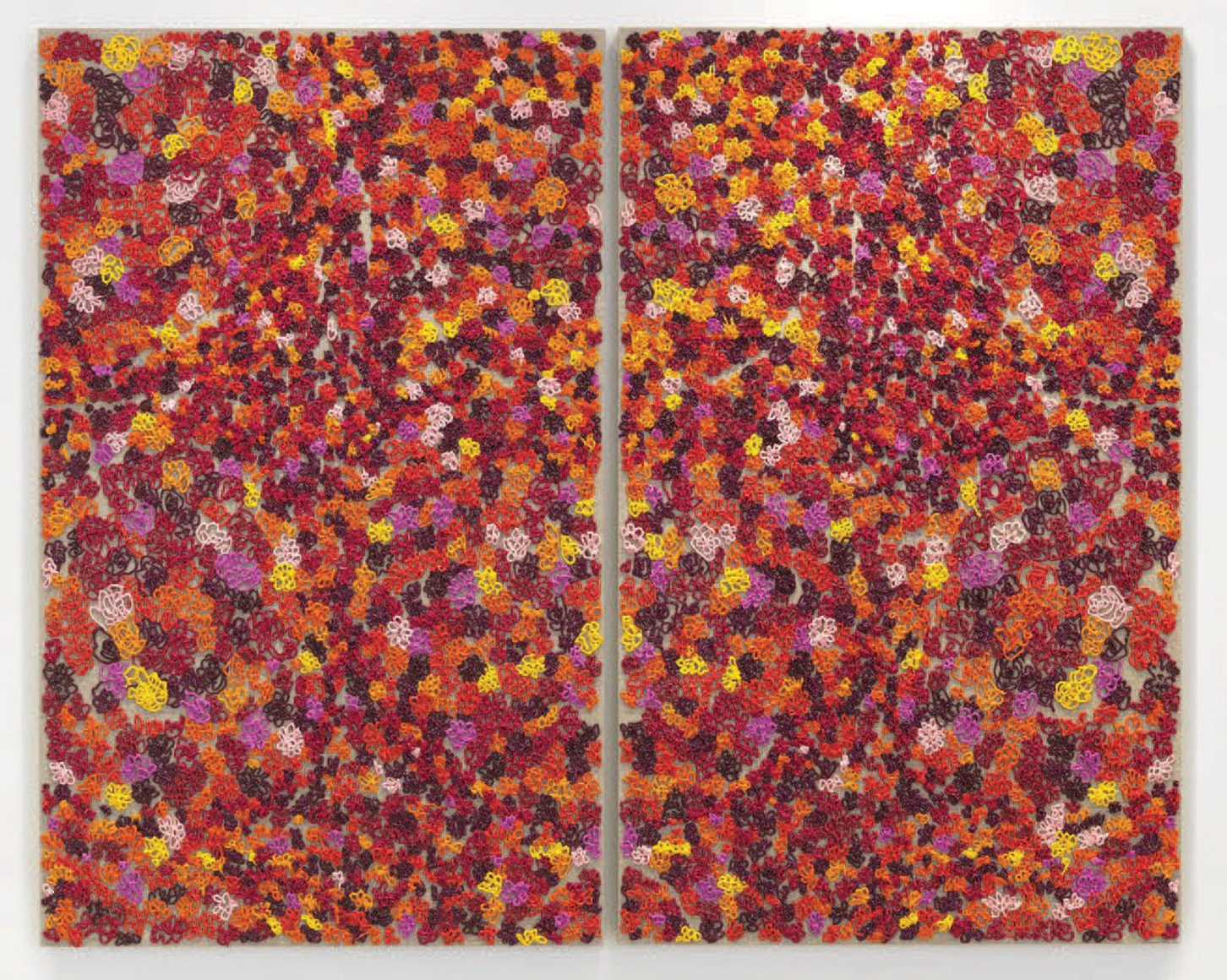

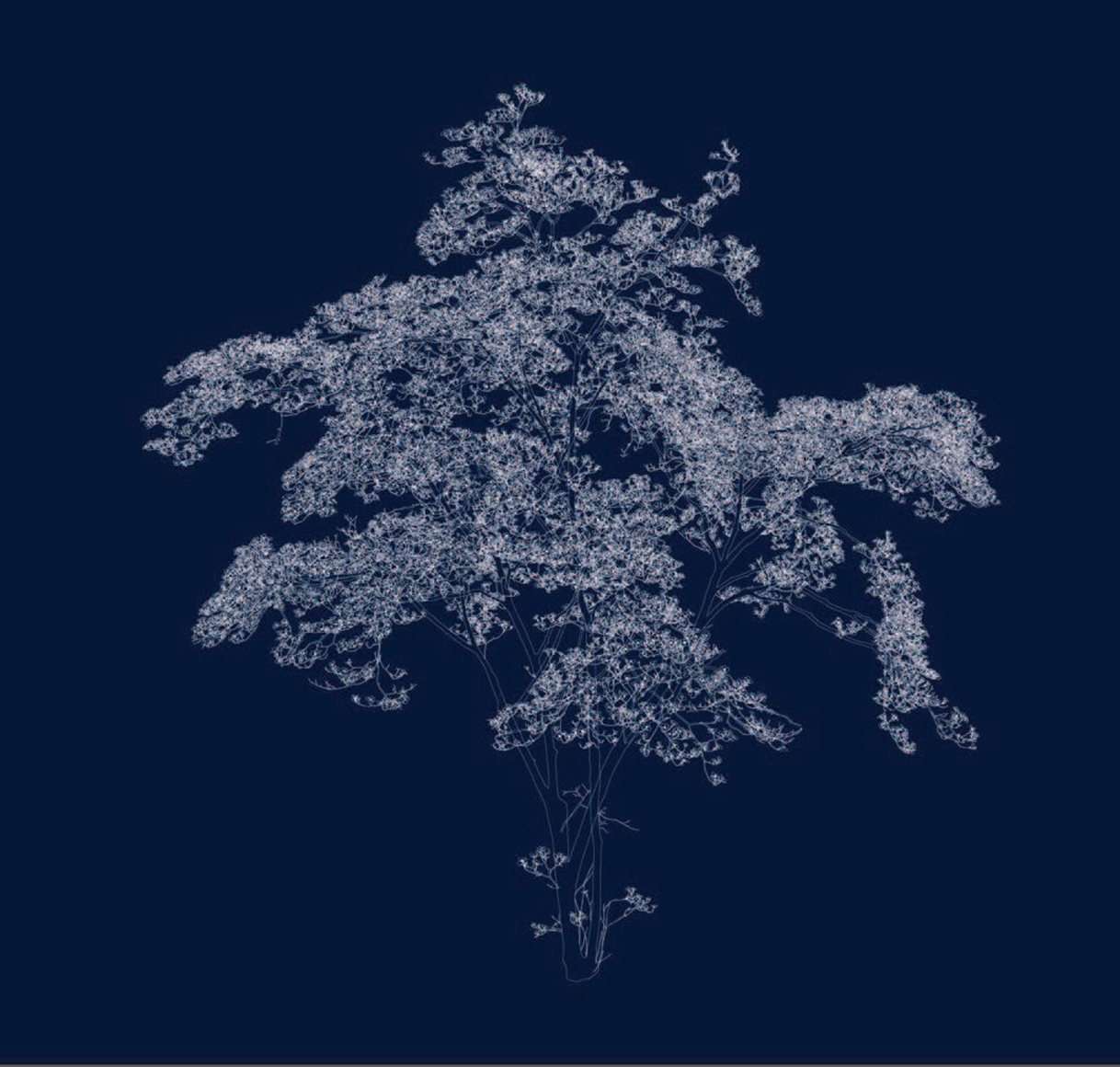

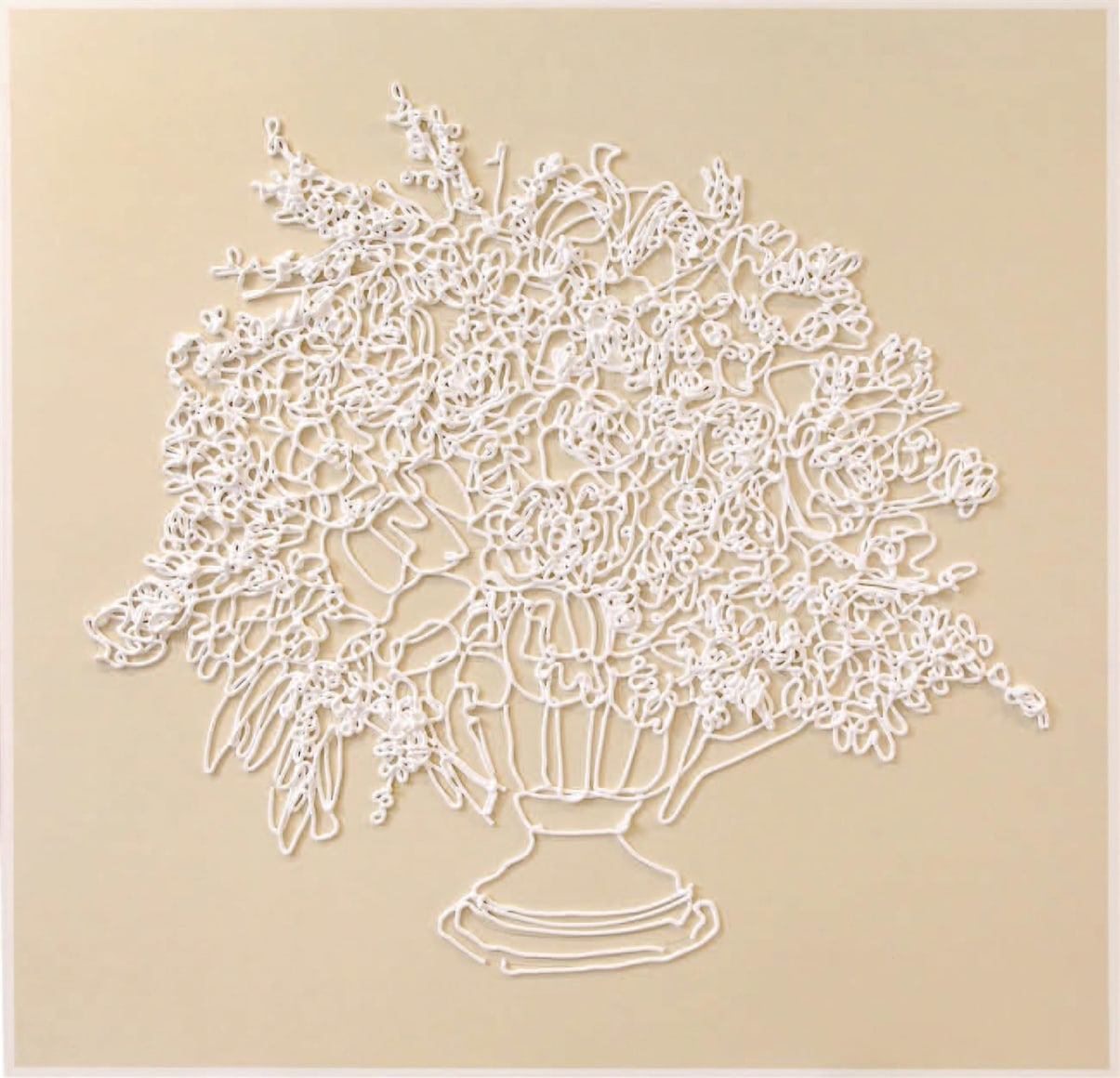

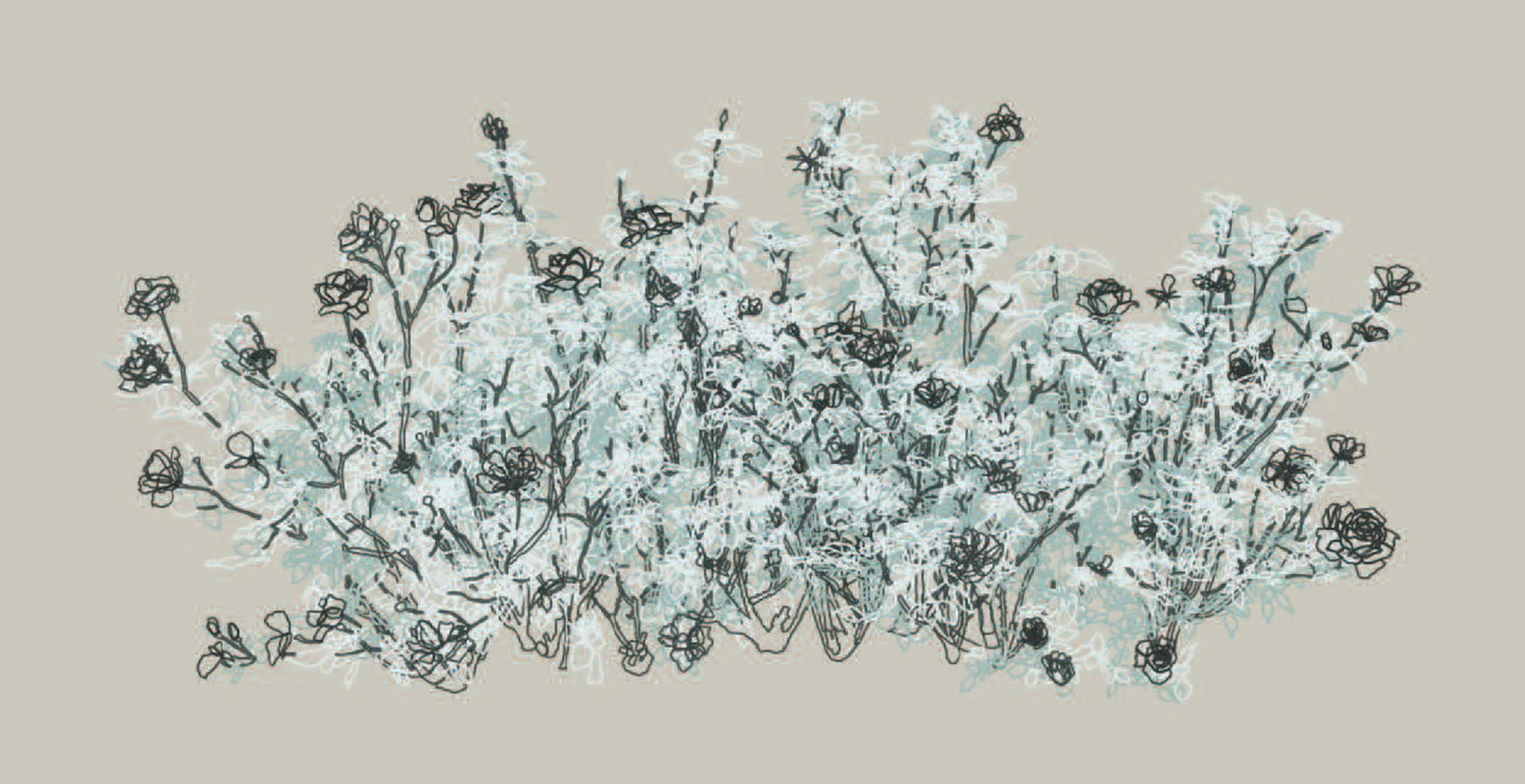

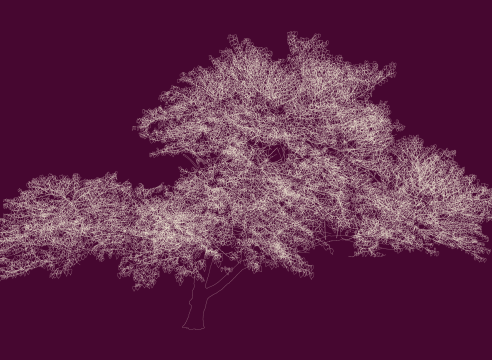

A Rorschach inkblot. A toxic cloud. A massive chandelier dripping thick magenta. When we look at Andrew Millner’s work, its figurative language stirs and distorts. Fractal-like florals pile on canvas; foreground and background conflate, compress. A pattern of roses shifts to a semblance more stark, foreign, looming. What was utterly two dimensions in the artist’s earlier work—digitized drawings of plants and trees presented in mind bendingly meticulous detail—become tactile here in dense acrylic. Around each lustrous conundrum of paint, naked canvas quietly spreads. Technically, these paintings resemble street graffiti as much as baroque wall hangings. They are majestic yet sprawling, deep while delicate, robust even though a little bit sad.

The eye struggles to make sense of it all. Is it pretty or disquieting? Flat or fantastic? But dichotomy serves to bolster the work, intensifying affect. Using drawings of rosebushes previously composed with a digital pen and graphics tablet, the artist projects the image onto raw linen canvas. He then carefully squeezes paint over the slender, winding lines, allowing it to pool at their intersections. What results can appear static from a distance, but up-close calls attention to the vagaries of chance. For as much as the artist controls the paint, gravity controls the distance it falls. But unlike the iconic drips that come from the “action painting” of the mid-20th century, Millner’s fall with precision. They are nearly parallel, yet eerily not, as each one plummets down by itself. Some drips bleed to the edge of the canvas, while others hover a few inches above. Some resemble Christmas tinsel hanging from a lampshade; others drop like earrings from the ends of stems.

Gertrude Stein famously claimed “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose” in her 1913 poem “Sacred Emily.” To Stein, whose creative and theoretical work anticipated postmodernism, language referenced itself as much as it did the tangible universe. A “rose” in a poem written during the modernist era (and, arguably, even more so today) reminds one not just of the bloom, but of the rich history of verse in which the proud flower was valorized. So, too, do Millner’s voluptuous figures reference multiple layers of information—mimetic and imagined, digital and “real”—to which we cannot have full access. Like Stein, he engages the law of identity, “A is A,” but Millner moves away from the rhetoric of thricefold repetition (“is a rose is a rose is a rose”) in his art-making process. His depicted roses do not chiefly reference a type of familiar flower, or even the digital photograph taken of the flower as the artist’s initial step. Millner’s “rose,” not unlike Stein’s, means more for what it could be than for what it surely is. What our eyes struggle to make sense of gains its own distinctive lyricism— an exercise in repetition that blurs the divide between technology, chance, and the artist’s hand.

-Eileen G’Sell